Trump pardons five former NFL stars, including a posthumous nod to Heisman winner Billy Cannon

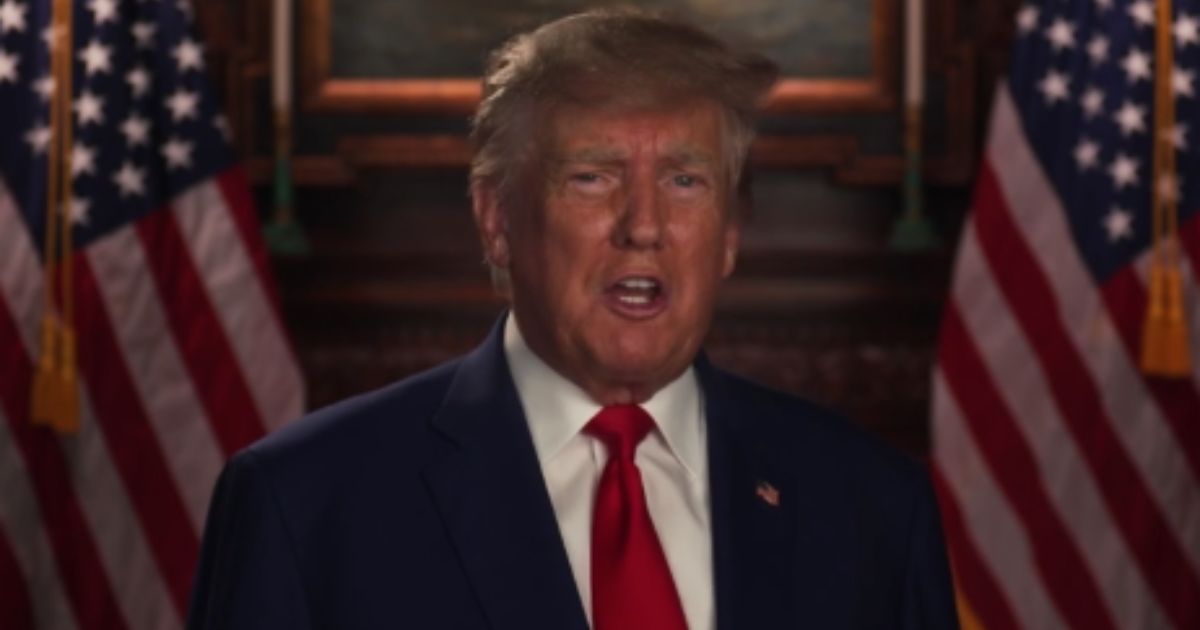

President Trump granted pardons Thursday to five former NFL players who were convicted of crimes ranging from counterfeiting to drug trafficking — a move announced by White House pardon czar Alice Marie Johnson, who framed the clemency as an extension of the administration's commitment to second chances.

The five players are: defensive tackle Joe Klecko, halfback Billy Cannon, offensive lineman Nate Newton, running back Jamal Lewis, and running back Travis Henry. Between them, they collected Hall of Fame honors, Super Bowl rings, a Heisman Trophy, and federal prison sentences.

Johnson posted the announcement on X:

"As football reminds us, excellence is built on grit, grace, and the courage to rise again. So is our nation…Grateful to @POTUS for his continued commitment to second chances. Mercy changes lives."

As of Friday, the President had not commented publicly on the pardons.

The Roster

Each of these men reached the top of professional football. Each fell. The details vary in severity, but the pattern is familiar — elite athletes who made serious mistakes after, or in some cases during, careers that millions admired.

Billy Cannon won the 1959 Heisman Trophy at Louisiana State University and delivered an 89-yard punt return against Ole Miss in Tiger Stadium that cemented his place in college football lore. He played 11 seasons across the AFL and NFL with the Houston Oilers, Oakland Raiders, and Kansas City Chiefs, earning two All-Pro selections. After football, Cannon became a dentist — then, in 1983, pled guilty to his role in a currency counterfeiting operation and served three years in prison. Cannon died in 2018 at the age of 80, making his pardon posthumous, as Breitbart reports.

Joe Klecko, now 72, anchored the New York Jets' legendary "New York Sack Exchange" defensive line. He recorded 20.5 sacks in the 1981 season — before the NFL even officially recognized sacks as a statistic — and finished his 12-year career with 78 sacks, four Pro Bowl selections, two All-Pro picks, and a 2023 Hall of Fame induction. In 1993, Klecko was convicted and sentenced to three months in prison on charges related to bankruptcy fraud tied to a business venture. He lied about false car insurance claims. The offense did not involve violence — it stemmed from financial misconduct.

Nate Newton, 64, won three Super Bowl championships as an All-Pro offensive lineman for the Dallas Cowboys. In 2002, he was sentenced for drug trafficking offenses, including possession for sale of hundreds of pounds of marijuana. Johnson noted that Dallas Cowboys owner Jerry Jones personally shared the pardon news with Newton.

Jamal Lewis, 46, rushed for 2,066 yards in 2003 — the third highest single-season total in NFL history — and won a Super Bowl with the 2000 Baltimore Ravens. In 2005, he pleaded guilty to using his phone to facilitate a drug transaction.

Travis Henry, 47, was a Pro Bowl running back who topped 1,000 rushing yards in three different seasons across stints with the Buffalo Bills, Tennessee Titans, and Denver Broncos. In 2009, he was sentenced to three years on federal cocaine trafficking charges, ending a seven-year NFL career.

The Case for Clemency

Presidential pardons are among the most personal exercises of executive power. They don't erase what happened. They signal that the country — through its chief executive — recognizes that a person's worst moment doesn't have to define the rest of their life.

That principle cuts across partisan lines, but it has particular resonance on the right. Conservatives understand that justice requires consequences. They also understand that redemption is real. A man who served his time, rebuilt his life, and contributed to his community has earned more than a permanent scarlet letter.

Klecko's case is the mildest of the five — a financial crime that led to three months behind bars, followed by decades of clean living and an eventual Hall of Fame bust. Cannon served three years and spent his remaining decades as a practicing dentist. Newton, Lewis, and Henry faced more serious drug-related charges, but each completed his sentence years ago.

None of these men was awaiting trial. None were avoiding accountability. The pardons restore civil rights and remove a stain — they don't undo justice.

Football, Failure, and What Comes After

Professional athletes occupy a strange space in American life. We celebrate their physical gifts and competitive fire, then act stunned when those same men struggle to navigate money, fame, and the abrupt end of a career that defined them since adolescence. That's not an excuse. It's a pattern worth recognizing.

The five men on this list committed real crimes. Counterfeiting. Fraud. Drug trafficking. These aren't technicalities or victimless offenses. But the question a pardon answers isn't whether the crime was serious — it's whether the person who committed it has demonstrated, over years or decades, that he's more than the worst thing he ever did.

Cannon can't benefit personally from a posthumous pardon. His family can. His legacy — the Heisman, the punt return, the dental practice he built after prison — gets to exist without an asterisk attached by the federal government.

Johnson's role as pardon czar has made her the public face of these decisions, and her framing wasn't accidental. She spent 21 years in federal prison before her own sentence was commuted. She knows what a second chance looks like from the inside.

Five pardons. Five men who reached the pinnacle of their profession, destroyed what they'd built, and then — in four cases — spent decades rebuilding. The fifth didn't live long enough to see the gesture, but his family did.

Mercy, when it follows justice, isn't weakness. It's the point.